View on YouTube

Pope Francis, in his speech on Thursday (September 24, 2015), invoked the "Golden Rule"--"Do Unto Others as You Would Have Them Do Unto You." At the turn of the twentieth century, the city of Toledo was governed by another staunch advocate of the Golden Rule: Samuel M. Jones, known throughout the country as "Golden Rule" Jones.

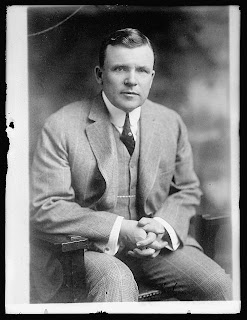

Samuel M. "Golden Rule" Jones, ca. 1900

Jones was born in 1846 near Beddgelert near Caernarvonshire, Wales. He emigrated with his family at age 3 to United States. Eventually the family settled in the Black River Valley in central New York, where Jones's father found work in a nearby quarry to supplement the meager living he could scratch out for his family as a farmer. By the age of 14, Samuel Jones was working in a lumber mill. At the age of 19, Jones struck out on his own for the oil fields of Pennsylvania, but returned home to New York after several disheartening months. After saving a bit of a nest egg, Jones returned to those Pennsylvania oil fields, eventually obtaining several oil leases of his own, marrying and raising a family with his beloved wife Alma. In 1881 however, tragedy struck. Jones's youngest child, daughter Eva Belle, died at the age of two. Four years later his wife also passed away. Deeply in grief, Jones's sister came to live with him to help him care for his two young boys; on the advice of friends, Jones struck out for the oil fields of west central Ohio in 1886. Jones drilled the first big well in Ohio, near Lima, which led to his joining with other oil producers to form the Ohio Oil Company. Within a couple of years, the group was "made an offer they couldn't refuse" by John D. Rockefeller, and Jones left the oil company business.

Samuel M. Jones and Helen Beach Jones, ca. 1895. Photo courtesy of the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library

While in Lima, Jones became heavily involved in the YMCA, and this led to his meeting Helen Beach, who was a member of a prominent Toledo family. In 1892 the couple, with Jones's two sons and his sister, settled in Toledo--the first time Jones had ever lived in a "large" city (Toledo's population was 81,000 in the 1890 federal census--up from 50,000 just ten years before). The Jones's arrived at an auspicious time--on the cusp of what was at the time the "great depression." Toledo's great period of expansion came to a screeching halt (temporarily), as workers drawn to the city to work in the glass, bicycle, foundry, and shipping industries were thrown out of work; 7,000 paupers were identified in Lucas County that year.

The work force at the Acme Sucker Rod Company, ca. 1895. Witnessing the poverty caused by the 1893 economic depression caused Jones to implement the 8-hour work-day; "Divide the Day." Photo courtesy of the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library.

The following year, after obtaining a patent on an improved "sucker rod" (the mechanism used to draw oil deposits underground to the surface), Jones opened the Acme Sucker Rod Company in an old abandoned factory in the Old South End in Toledo, on Segur Street near Broadway, to manufacture his new sucker rod. Greatly disturbed by the upheaval he had witnessed during the early year of the depression, Jones had but one rule that governed his factory, "Therefore Whatsoever Ye Would That Men Should Do Unto You, Do Ye Even So Unto Them"--the Golden Rule. Jones also paid his workers $1.50-$2.00 per day when the "going rate" in Toledo was $1.00-$1.50 a day. Jones also cut the work day for his workers to 8 hours from 12, and gave them a week's paid vacation after 6 months on the job. Later, he bought an empty lot next to his factory and created a playground and a park for the neighborhood, where children played and people could listen to music or speakers Jones brought to the city (including Jane Addams and Eugene Debs).

A crowd at Golden Rule Park, ca. 1895. Photo courtesy of the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library

Jones entered local politics in 1897 as a "compromise" candidate for the factionalized Republican Party; he wasn't well-known enough to antagonize one side or the other. That changed shortly after his election, after defeating his Democratic opponent by a scan 518 votes out of the 20,164 cast. Jones vision for a city governed by the Golden Rule included taking away the clubs of the police, who were issued walking sticks instead. Jones also instituted a merit system for both the police and fire departments, and refused to enforce Sunday "blue laws" that were suppose to shutter saloons--and he also refused to prosecute prostitutes, claiming that running them out of town--as the "better" citizens demanded--only moved the problem to another location.

"Golden Rule" Jones and Brand Whitlock, in the Mayor's office, ca. 1900. Photo courtesy of the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library

By the time of the 1899 municipal election, Jones had fallen out of favor with the local Republican Party, which refused to re-nominate him. Jones chose to run an a political independent on the slogan "Principle Before Party"--and defeated both the Republican and Democratic nominees handily, winning 70 percent of the vote. Later that year, Jones was persuaded to run for governor later that year, a prospect that struck such fear into the heart of the national Republican Party that they pulled out all stops to defeat him. Party luminaries like Spanish-American War hero and Republican governor of New York Theodore Roosevelt, US House Speaker David Henderson, US Senate President Pro-Tem William Fry, both sitting Ohio US Senators--even President William McKinley himself (who, in the practice of the time, didn't even campaign for himself for office in 1896) campaigned against Jones and for the Republican nominee George Nash, who defeated Jones in the fall election, despite Jones winning both Toledo and Cleveland by substantial margins.

Where's Teddy? Theodore Roosevelt lost in the crowd in Toledo, ca. 1899. Photo courtesy of the Toledo-Lucas County Public Library.

Despite this electoral defeat, Jones won re-elections in Toledo in both 1901 and 1903, although never again approaching a 70 percent victory margin. After a brief illness, Jones died in office in 1904. 55,000 people viewed his body as it lie in state, and 5,000 Toledoans attended his funeral. After his death, his family learned that the value of his estate, thought to be in the neighborhood of $900,000 (more than $25 million in today's dollars) had dwindled to just $300,000; Jones had given away much of his money or used it to finance the Acme Sucker Rod company's profit-sharing plan; Jones apparently also took the biblical admonition that "It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the kingdom of God" to heart as well.

Brief bibliography

Marnie Jones, Holy Toledo: Religion and Politics in the Life of "Golden Rule" Jones (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1998).

Tana Mosier Porter, Toledo Profile: A Sesquicentennial History (Toledo: Toledo-Lucas County Public Library, 1985)